Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Discover why the UK market is shrinking and what it means for investors and the economy

The shrinking UK stock market is a worry for fund managers and has wider implications for the UK as a listing venue as well as the UK’s economic growth, say analysts at Peel Hunt.

This article explores the so-called de-equitisation of the UK stock market, or plainly put the substitution of debt for equity via share buybacks and cash acquisitions.

More than 45 companies exited the UK market in 2023 due to takeovers and the pace shows no signs of slowing. In fact, the run rate so far in 2024 is double 2023’s level based on data compiled by AJ Bell investment director Russ Mould.

Mould estimates takeovers added between 1% and 2% to total cash returns over the last year, on top of around 4% from dividends and 2% from share buybacks.

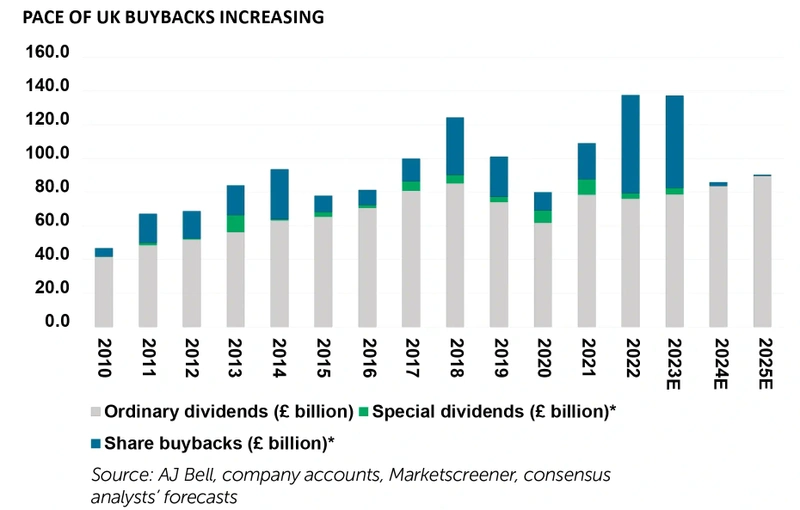

Buybacks have also been increasing in recent years. Fund managers Laura Foll and James Henderson at Lowland Investment Company (LWI) point out that 2.5% of the FTSE 350’s market capitalisation disappeared via share buybacks in 2022.

Based on Morgan Stanley data, fund manager’s at Redwheel show the UK top is top of the global heap in terms of total yield (dividends plus share buybacks). Total yield from the UK stock market is just over 6%, nearly double that of the US.

This makes the UK the most attractive market on this measure in the developed world, which goes some way to explaining the increasing pace of opportunistic takeovers.

Similar evidence from a different source is provided by fund manager Victoria Stevens of the Liontrust (LIO) Economic Advantage team. Stevens points to Canaccord Genuity’s Quest valuation model which shows UK smaller companies have the biggest upside to fair value among developed market regions.

UK managements are also recognising value in their own companies and directing more cash towards share buybacks.

For example, half of all UK companies undertook a share buyback in 2023 compared with a third of European companies, according to Morgan Stanley.

Making matter worse, companies leaving the UK market are not being replaced by new companies joining the market. Peel Hunt points out the bottom of the ‘hopper’ is not getting refilled by new companies floating on the market as IPO’s (initial public offerings) have dried to a snail’s pace over the last 12 months.

WHY IS THIS A PROBLEM?

The average takeover premium to the undisturbed share price in 2023 was 51% according to Mould, and given the takeovers added yield to shareholders’ pockets investors might be wondering why this is a problem.

Peel Hunt presents a list of reasons why this is generally bad news for the UK. For starters, most of the takeovers happened in small- and mid-cap companies which are genuinely growing and adding jobs unlike their larger brethren which are shrinking their workforces.

The list of small caps captured by buyers includes car dealer Lookers, funeral provider Dignity and teleradiology services firm Medica plus Wagamama-owner Restaurant Group and ten-pin bowling play Ten Entertainment.

With promising growth companies leaving the market, London is becoming a less attractive place to list. This further reduces sector peers and depth of knowledge, argues Peel Hunt.

This is most obvious in technology with recent departures of Aveva, Avast and Ideagen, while Emis, Mediclinic, Medica and Vectura are examples from the healthcare sector.

All these factors create a ‘circularity of negativity’ where ‘valuations are low, liquidity is depressed, and companies exit the market as long-term prospects/valuation are not being adequately recognised’ concludes Peel Hunt.

Excluding investment companies, Peel Hunt estimates the total number of firms has shrunk by 10% over the last decade.

It is not just a UK phenomenon. Former Citigroup (C:NYSE) global chief equity strategist Robert Buckland points out de-equitisation has even taken hold in the US.

Available stock in public markets has shrunk by 1% per year since the start of the century says Buckland, and even the mighty technology sector has not been immune driven by huge share buybacks from the likes of Apple (APPL:NASDAQ).

A SELF-INFLICTED PROBLEM

As for the UK, Buckland offers a simple explanation for the shrinking stock market.

Domestic institutions switched out of UK stocks into bonds partly to adopt liability-driven pension fund strategies. This created a wide disparity in valuation between the two asset classes.

In 1997, pension funds allocated just over half their portfolio to UK equities compared to less than 5% today according to the think tank New Financial.

Even accounting for higher interest rates, UK corporates can still borrow at 6% in corporate bond markets to buy assets on the stock market generating an earnings yield of 9% argues Buckland.

‘It makes little sense for listed companies to issue more equity or unlisted companies to float,’ says Buckland.

The US equity market trades on a similar earnings yield to the corporate bond market which makes de-equitisation less compelling.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

One possible answer according to Michael Tory, co-founder of investment banking boutique Ondra Partners, is to decouple defined-benefit pension schemes from corporate sponsors and consolidate into a handful of superfunds.

Some commentators point to the success of the Welcome Trust, a charitable foundation funded by a £37 billion investment portfolio which has averaged almost 12% annual returns over the last two decades.

The UK chancellor’s initiative to encourage pension funds to take on more investment risk by investing in younger companies and infrastructure projects is an attempt to change the status quo.

Alongside the introduction of a new £5,000 UK ISA, it will be interesting to see if these actions turn sentiment towards UK equities around.

Asset manager Invesco takes a positive stance: ‘If just 200,000 ISA investors allocated this additional £5,000 to the UK smaller companies’ sector, the £1 billion of extra funding would represent a sector record over the last two decades and would help boost the overall health of UK public equity markets.’

DISCLAIMER: AJ Bell referenced in this article is the owner of Shares magazine. The author of this article (Martin Gamble) and editor (Tom Sieber) hold shares in AJ Bell.

WHY DID THE UK CHANGE THE PENSION RULES

UK pension funds have been moving away from shares into bonds and alternative assets to lower the risk of meeting pension fund obligations. Mark-to-market accounting rules and tighter regulation over funding levels have played a key role.

The regime change was sparked by the accidental death of media mogul Robert Maxwell who was believed to have fallen overboard from his yacht. After his death, it transpired Maxwell had been using some of the Mirror Group’s pension assets to prop up his business empire.

The resulting furore created a public backlash and pressure to bring in new rules to protect pension members of defined-benefit schemes. These make payouts to retired members based on salaries and the number of years worked.

Economist John Kay describes the resulting series of tax, regulatory and accounting changes as ‘one of the great avoidable catastrophes of British public policy’.

‘You had a system that worked pretty well, which was replaced by one that constrained investment strategies and effectively killed UK private sector defined-benefit schemes,’ says Kay.

The shift from equities to bonds has not been apparent in other global pension markets according to a study by pension consultants Willis Towers Watson and New Financial.

John Bell, chair of UK biotechnology success story Immunocore (IMCR:NASDAQ), which decided to list in the US because it could not find capital in the UK, told the Financial Times: ‘We have trillions of pounds sitting in UK pension funds that are not being used to invest in companies, drive growth or do a whole range of things that the economic viability of the country depends on.

‘We need to find ways to release this capital,’ adds Bell.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

magazine

magazine