Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Is it time for emerging markets to pop higher?

In the coming week (22-24 October), Russia will host the latest annual BRICS summit in Kazan. For all that one of the meeting’s key goals is to tackle neglected tropical diseases, few investors may be inclined to pay attention, not least given the economic sanctions imposed upon the host nation. The concept of the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (the BRICS) as an investable grouping is not as popular as it was either, more than 20 years after (then) Goldman Sachs (GS:NYSE) banker Jim O’Neill first coined the phrase, partly because of geopolitical, or local political, trends; partly because of economic woes, notably in South Africa; and partly because of the bursting of stock market and then property bubbles in China in 2015 and 2023 respectively.

Yet India’s headline Sensex stock market index trades at all-time highs, as does Brazil’s BOVESPA and South Africa’s JSE All-Share benchmark. China has been the one to let the side down, as until recently the CSI 300 had traded no higher than it did in 2007.

Fresh measures from Beijing to stimulate its flagging economy have given the headline indices in Shanghai and Hong Kong a huge boost, as they have gone from worst to first among global equity benchmarks in 2024.

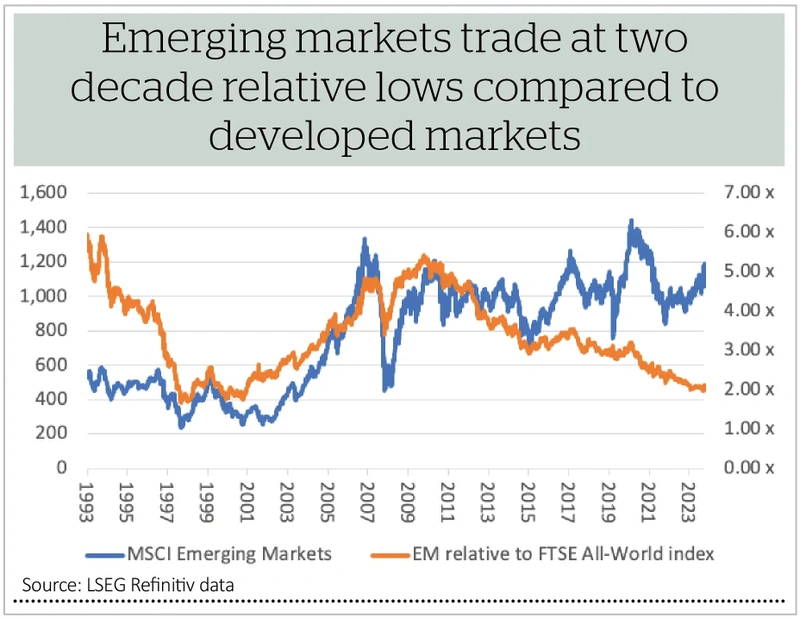

So downbeat was sentiment, and so lowly were valuations, that it took relatively little to stoke fresh interest. It remains to be seen whether the recovery can be sustained, but this is a timely reminder that emerging markets overall have underperformed developed markets for more than a decade. On a relative basis, emerging markets trade no higher now compared to developed markets than they did in 2001, after which point the bursting of the tech bubble and return to favour of cyclical, value stocks brought emerging markets back into favour.

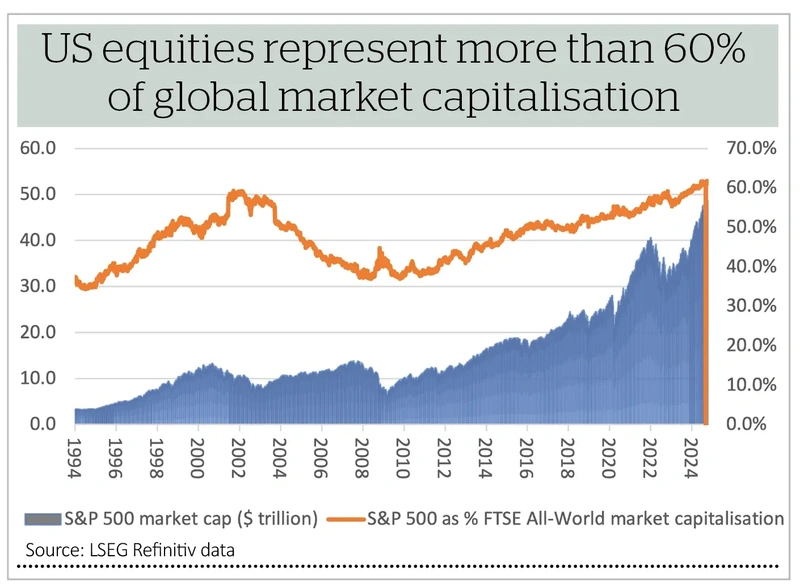

Contrarian investors could therefore be forgiven for asking themselves whether it is now time for a fresh look at emerging markets, given the world is once more in thrall to tech stocks and US equities in particular.

HIGH LEVELS OF INTEREST

China and Hong Kong have given one hint of what could be a potential catalyst for stronger performance from emerging markets, in relative and absolute terms, namely fiscal and particularly monetary stimulus. Beijing has cut interest rates, lowered the amount of capital that banks had to hold (so they could lend more) and eased the rules on consumer purchases of property.

There is still much more to do, if China is to sustainably boost growth and ensure that consumption becomes its main economic engine instead of construction and exports, and the July’s proposals for land reform at July’s Third Plenum offer a hint of what may be to come.

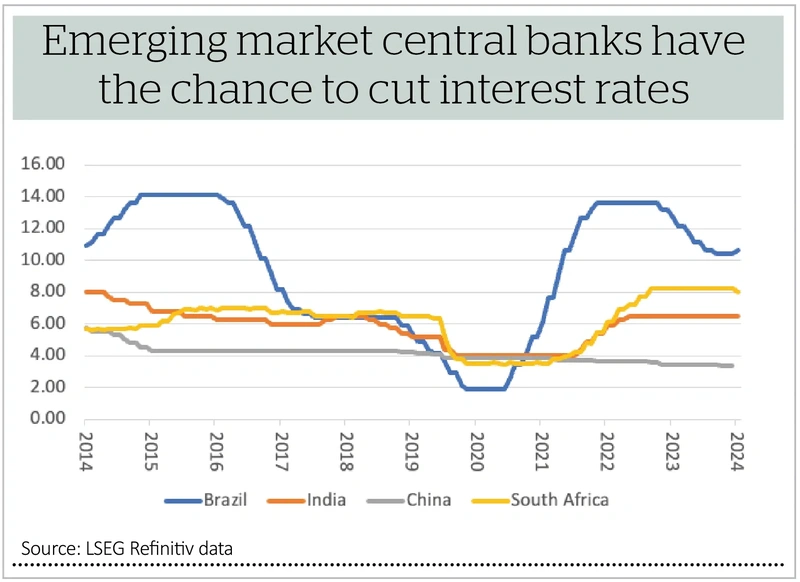

More widely, interest rate cuts could help emerging markets, whose central banks were generally quicker to hike headline borrowing costs as inflation broke out in the wake of the pandemic. They now have scope to cut rates, especially as the US Federal Reserve has started to do the same. Emerging markets have had to wait, because their currencies would have weakened (and given inflation fresh impetus) had they moved before the Fed.

Lower rates could boost local GDP growth and benefit corporate earnings across markets which can be heavily exposed to cyclicals and financials, and other economically sensitive sectors, either domestically or across international markets.

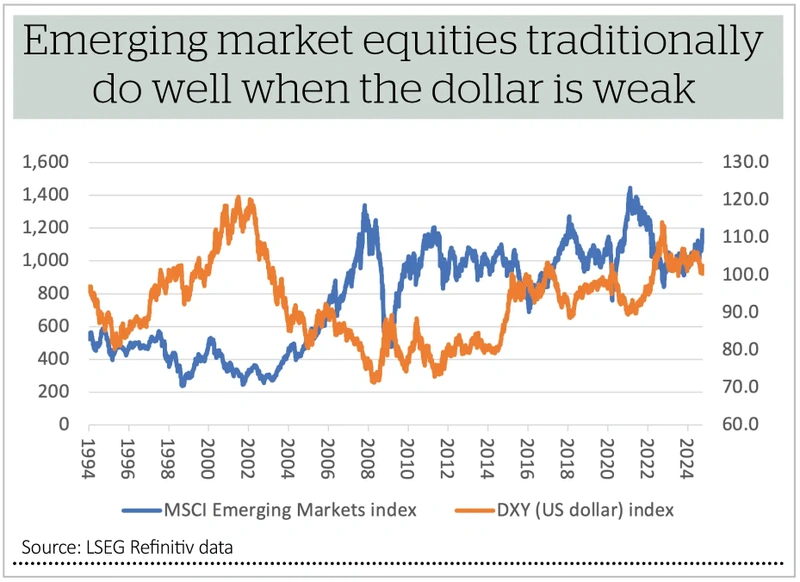

If the Fed really gets going on interest rate cuts, then the dollar could weaken. A drop in the buck, as benchmarked by the trade-weighted DXY (or ‘Dixie’) index, is traditionally seen as helpful for emerging markets, especially those with dollar borrowings. Lower rates and a softer dollar lower the cost of servicing those overseas debts and the reduced interest bills leave scope for more pro-active government investment elsewhere.

RAW MATERIALS

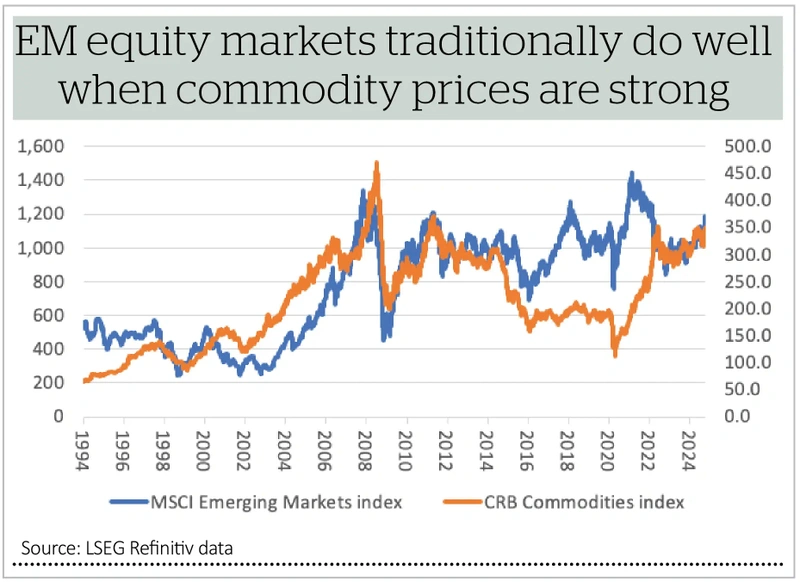

If interest rate cuts and a weaker dollar are two possible catalysts for improved emerging market equity market performance, then a third is strength in commodity prices.

This could reflect how some emerging markets are key producers and exporters of raw materials, notably Brazil and South Africa. It may also be the result of how emerging markets are plugged into global growth more widely through their exports (and if global growth is strong then demand for commodities is likely to be elevated). Commodities can also do well when inflation is running strongly, as investors seek havens and assets that can protect wealth relative to cash and paper assets, and also feel less inclined to pay up for secular growth assets when cyclical growth is more freely (and probably cheaply) available from value plays, such as emerging markets.

The dangers to emerging markets are therefore that the US cuts rates more slowly than thought, the dollar gains ground, inflation remains subdued and commodity prices soften, to continue the world’s love affair with tech and America – in other words, the trends of the last two decades continue for the next one. Investors can only decide for themselves how likely they think this is.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

magazine

magazine