Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Time to follow the money

The American financial markets writer and publisher Jim Grant once observed that: ‘Successful investing is having everyone agree with you …. Later.’ This makes perfect sense, as it distils the concept of going against the crowd to buy cheaply and then sell expensively to lock in the gain and the initial thesis is now the consensus view and thus reflected in the valuation.

However, this column does wonder whether there may be one instance, at least, where following money flows could be useful. It can be found in the field of macroeconomics and the trend in question is growth in money supply, because it might just be the most reliable indicator when it comes to fathoming where inflation goes next.

And if investors have a view on where inflation goes next, they can formulate a view on where interest rates go next and if they have a view on interest rates then that can help to forge their strategy when it comes to a whole host of asset classes, ranging from equities to bonds to commodities to cash and cryptocurrency.

MONETARIST MEMORIES

The University of Chicago’s Milton Friedman is seen as the leading exponent of monetarism, a theory whereby the quantity of money (and its velocity) is a key factor in the rate of inflation. Margaret Thatcher, encouraged by Alan Walters and Keith Joseph, latched on to the concept when she became Conservative Party leader in 1975 and as a team, they applied it with rigour during her term as prime minister from 1979 to 1990.

The initial results were government spending cuts, soaring interest rates and – detractors would argue – a recession and lofty unemployment. Supporters will argue that the long-term benefits were huge decreases in the rate of inflation, a problem that had bedevilled the 1970s, and an economic boom that only hit the buffers in the early 1990s.

But now Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey talks of being data dependent, with a particular focus on jobs and inflation. Similar noises come from Jay Powell and the US Federal Reserve.

This seems odd when a clear case can be made that the monetary and fiscal stimulus applied during the Covid pandemic had a major role to play in the subsequent spike in inflation, on both sides of the Atlantic.

PRICE AND SUPPLY

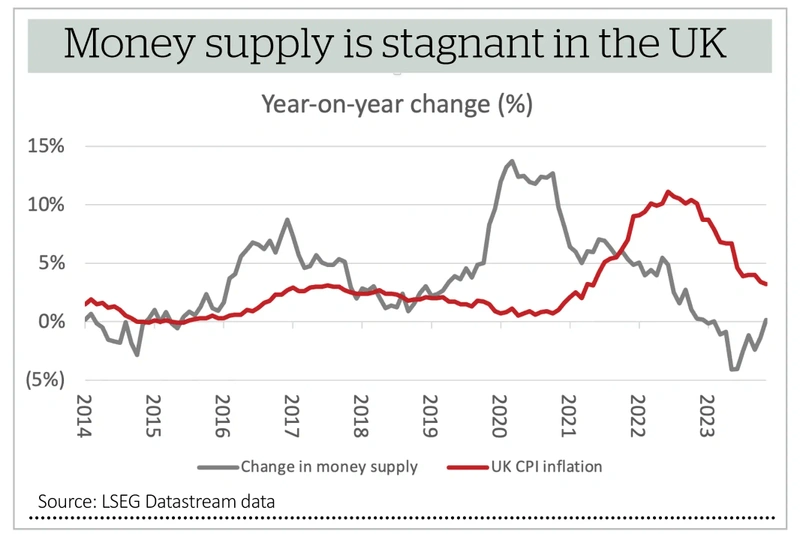

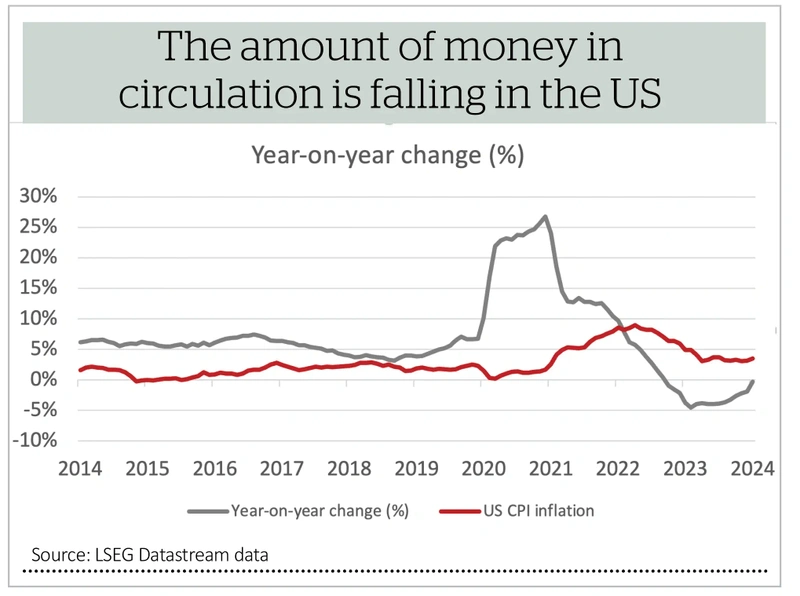

Note how zero interest rate policies and quantitative easing (QE), when coupled with government borrowing, drove double-digit percentage year-on-year growth in the supply of money in America and the UK.

Basic economics teaches us that the price of something goes down when its supply increases, especially when the supply increases a lot.

The same applies to money. More of it was created during the pandemic, to stave off a feared economic meltdown. But there is no such thing as free money and now we have to foot the bill, in the form of higher taxes and debt repayment (reduced money supply), higher interest rates and quantitative tightening (reduced money supply) or higher inflation (reduced value of money). It is not an appetising list, but we are where we are.

NOTHING TO SEE HERE

Unsurprisingly, central banks do not wish to be seen as the architect of this misfortune and are blaming Covid, supply chain blockages, crashed ships in the Suez Canal, wars and oil price spikes for the surge in inflation. But a study of money supply growth relative to inflation suggests that the former is a lead indicator for the latter.

The good news for central bankers is their efforts to restrain money supply through higher interest rates are working. There is no growth in money supply at all in the UK and in America it is falling. This suggests inflation may cool further.

Central bankers may therefore be justified to inching their way toward interest rate cuts. That could, in theory, be good for bonds and good for equities, as lower rates stoke demand for credit, demand for goods and services and lower interest bills, to the benefit of corporate earnings. They also reduce discount rates in discounted cashflow calculations and raise the net present value of future cash flows and thus theoretical equity valuations.

BALANCING ACT

If policymakers leave rates too high for too long, and squeeze money supply too hard, the result could be deflation and that would be a disaster, given the levels of government indebtedness on both sides of the pond. (The West would indeed turn Japanese as economic growth and corporate earnings power would hit a wall). The response then would probably be fresh rate cuts and more QE.

Equally, there is a residual danger that central bankers cut too early. The rate of change in the rate of change of money growth looks to be accelerating again so too much stimulus could lead to a fresh inflationary outburst, especially as unemployment is low and wage increases exceed inflation.

The outcome then could indeed be higher rates for longer and the sort of austerity and recession that purge inflation but hurt share prices at the same time.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Editor's View

Feature

Great Ideas

News

- ITV up 30% as streaming platform proves its worth

- UK IPO market hots-up after Shein accelerates plans for London listing

- UK takeovers and premiums back to record levels of 2018

- Intel dealt Huawei blow by US government

- Bruised Palo Alto investors praying for improvement

- Sky-high expectations leave no room for earnings disappointment

magazine

magazine