Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Will the third plenum prime fresh interest in China?

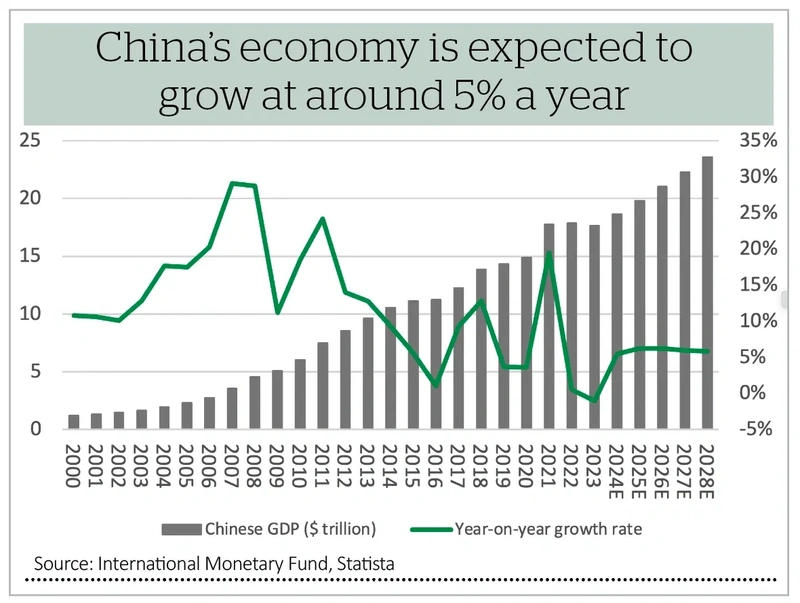

For all of its current challenges, China’s economy is still the second largest in the world, trailing that of only America. According to data from the International Monetary Fund, Chinese GDP had from $1.2 trillion in 2000 to almost $18 trillion in 2023 (and thus as big as Germany, Japan, India, the UK and Brazil combined). That is a compound annual growth rate of 12.4%.

Yet for all of this phenomenal progress, the Chinese stock market has offered much less joy to shareholders and investors. The economy may have grown nearly 14-fold since the end of the last millennium, but the Shanghai Composite index is up by just 120% – a compound annual return on capital of just 3.5%, miles below GDP growth.

There are three pertinent points here. The first is that using macroeconomics to pick stock markets or individual stocks is a likely road to disappointment, as the two do not follow as closely as the casual observer would expect. The second is that financial bubbles really do serious damage. China has had two stock market boom-and-bust cycles since 2000 and it has a third one on its hands now, this time in real estate.

The final one, therefore, is that the quality of the growth matters more than the quantity. China has switched its focus from domestic construction and infrastructure to exports and now to domestic consumption in its quest for growth, but an increased reliance upon debt, and property speculation, meant the quality of growth has deteriorated (and the quantum has begun to suffer as a result).

This third point in particular takes us to the next major meeting of the Communist Party’s central committee, or plenum, which is due in July. What emerges from this may help to set the tone for the Chinese economy (and perhaps its financial markets) for some time to come.

PARTY GAMES

China is finding it harder and harder to generate robust economic growth, and not just because of the law of large numbers. In dollar terms, the economy more or less flatlined in 2023 (thanks the greenback’s strength against the renminbi) and grew by 5.3% in local currency, and that came after a modest 3% advance (in local terms), as China staggered out of the pandemic and lockdowns and walked straight into a spectacular real estate bust.

This why so many China-watchers are looking toward the third plenum political cycle. There are usually seven plenums during the five-year life of each 370-strong Central Committee and the third one is usually seen as a platform for reform and the formulation of economy policy.

Research from the South China Morning Post flags how the third plenums of 1978, 1993 and 2013 in particular, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and current leader Xi Jinping, all laid out major reform programmes designed to boost growth. Given China’s current struggles, expectations are gathering that something big is coming, especially after the postponement of this third plenum last autumn.

CURRENCY CONUNDRUM

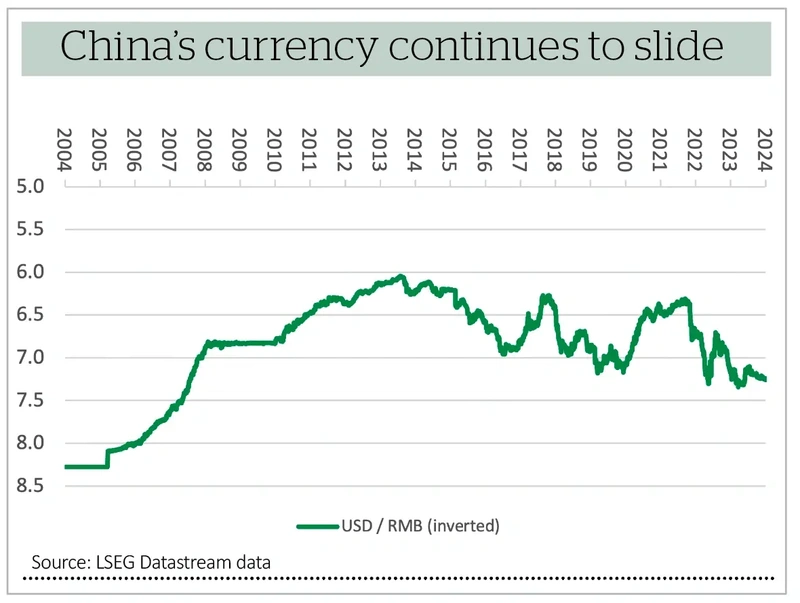

The financial markets seem pretty convinced that China has a growth problem, thanks to the real estate bust, build-up of unproductive debt and growing geopolitical pressure that means the West is busily erecting trade barriers to keep out cheap Chinese goods, or obstruct their development, where it can. This may be why its currency keeps sliding lower – markets are expecting either an interest rate cut or an outright adjustment of the value of the renminbi (in effect a devaluation), which is trading near levels last seen in 2008, in the view that it cannot manage interest rates, a quasi-pegged currency and facilitate free capital flows all at the same time.

China does not permit free capital flows anyway but if Beijing wishes to extract itself from the dollar’s orbit, then it may have to entertain this notion at some stage. Equally, permitting a devaluation would not help in this economic and geopolitical aim and nor would it really boost the economy much either, since China already runs a big trade surplus, and it is facing ever-greater barriers in the West to its exports anyway.

If China is having to move away from infrastructure and property development, and cannot use exports as an economic lever, then that really leaves domestic consumption and perhaps that is where the plenum will focus its attentions, especially as growth in retail sales (and thus demand) is still running below growth in industrial production (and therefore supply).

Whether this can benefit investors in Chinese equities, directly (or more likely through passive trackers) or overseas companies that may benefit from increased Chinese consumption, is harder to divine. The iShares China Index ETD is one-third weighted to consumer discretionary names, for example, but history suggests that any policies that come from the plenum will be run to suit the Communist Party and its political and economic agendas, and not for the benefit of equity markets and overseas shareholders, something that investors will need to factor into any risk and valuation considerations.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

magazine

magazine