Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

How to ride central bank rate cut cycles (without falling off)

Interest rate cuts in the month of August in the UK, Sweden and New Zealand, to name but three, take the global total to 108 this year, according to the website www.cbrates.com. That is more than 2022 and 2023 combined, and the US Federal Reserve is now dropping very unsubtle hints that it will be joining in at the next meeting of the Federal Open Markets Committee on 18 September.

This all seems to be in keeping with the core narrative that is doing so much to boost equity and government bond markets alike, namely that inflation will cool, economies will enjoy a soft landing (if indeed there is any landing at all in the US) and that central banks will therefore be able to cut the headline cost of money.

Those rate cuts are in turn expected to stimulate demand for credit and thus economic activity, boost corporate earnings and cash flows thanks to higher demand (and lower interest bills) and persuade investors to take more risk, with asset classes such as equities, as the yield available from cash and fixed-income decline.

Such a scenario sounds very beguiling, but market history suggests equity investors might like to be a little careful about what they wish for, with regard to monetary policy for three reasons, even if the FTSE All-Share and S&P 500 have, on average, benefited from cheaper money on a two-year view, once the initial rate cut has been announced:

First, equity markets do not always initially respond favourably to rate cuts, not least as they have had time to price in the first moves, and volatility often ensues, as markets assess the reasons for the reductions (victory against inflation, a recession or a financial crisis).

Second, rate cuts did nothing to stave off recessions (or equity bear markets) in 2001-03 and 2007-09 when corporate earnings estimates fell faster than borrowing costs and lofty valuations proved unsustainable.

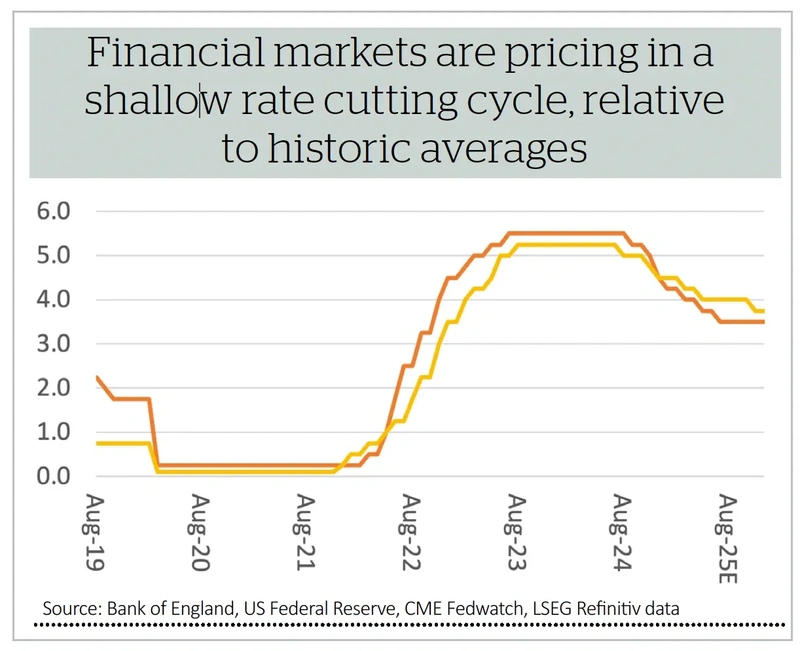

Finally, the Fed and the Bank of England cut by an average of four-and-a-half percentage points from peak to trough during a typical downcycle. That is more than markets are expecting this time around, to suggest that equity and bond markets may be underestimating how far central bankers may move – to the potential detriment of the former (if they have to go that far, then an unexpected economic downturn would presumably be the most likely cause) and benefit of the latter (at least unless stagflation takes hold).

CUT AND RUN

Faith in the US Federal Reserve’s ability (and willingness) to support stock markets dates back to when then-chair Alan Greenspan waded in with a pair of quick-fire interest rate cuts and a $3.6 billion bail-out plan in the wake of Russian debt default and the collapse Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund in 1998. That set the scene for another leg-up in the 1990s US equity bull run. Since then, central bankers have responded with interest rate cuts, quantitative easing and other unconventional tools and interventions to the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09, the European debt crisis of the 2010s, dislocations in the American inter-bank lending markets in 2019, the pandemic in 2020 and a US (and Swiss) banking wobble in 2023.

All of these actions helped financial markets, ultimately, to come through relatively unscathed although sceptics may latch on to the words ‘ultimately’ and ‘relatively.’ Even former Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram Rajan has opined recently in the Financial Times that central bankers should set a higher bar for interventions, so that their quest for financial and economic stability does not provide too big a safety net, encourage risk taking and promote the very instability they were seeking to avoid as a result.

The way in which the post-LTCM rate cuts helped to stoke the technology, media and telecom bubble of 1998-2000, and asset prices have soared across the board since 2009 support that view. Moreover, it does seem as if recessions now happen less frequently but come with greater severity when they do, while financial crises feel more common.

NIP AND TUCK

To start with the UK, the good news is that over the thirteen rate-cut cycles since the inception of the FTSE All-Share in the early 1960s, the index has made an average gain of 16% in the two years after after the first decrease in borrowing costs. Yet the hit rate over the first three to six months is patchy and the 2001-03 and 2007-09 rate-cutting cycles started disastrously for buyers, with losses over a two-year period as recessions bit hard, earnings disappointed and equity valuations faltered.

The two-year post-cut performance from the S&P 500 is similarly compelling, on average, but again the trick for investors is to safely navigate the volatility in between. The S&P 500 historically does not make much initial progress after the first cut, not least because it runs up strongly in anticipation.

The scenario that markets are still discounting is lower inflation, a soft landing and a gentle reduction in rates. If anyone of those three trends diverges from current expectations, then equity markets may move, potentially with some violence, as we saw briefly back in August.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Editor's View

Great Ideas

Investment Trusts

News

- Why investors have dumped Dollar General stock

- Burberry exits FTSE 100 after 15 years but EasyJet looks to have dodged relegation

- Shares in maritime artificial intelligence company Windward are flying

- Gym Group raises outlook ahead of first-half results

- Investors bet on Rolls-Royce recovery after engine trouble sparks sharp sell-off

- US non-farm payrolls in the spotlight after Jackson Hole speech

- Oracle facing growth acceleration acid test

magazine

magazine