Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Will money supply be a snake or a ladder for economies in 2025?

China’s New Year Holiday festival is over, and the Year of the Snake is now under way. People with a much keener interest in, and better understanding of, the Chinese zodiac tell this column the snake signifies intelligence, mystery and renewal.

Make of that what you will, but president Xi Jinping and the Communist Party authorities are going to need plenty of the first trait if they are to resolve the second and prompt the third when it comes to China’s economy and how to turn it around.

A real estate bust, coupled with the need to move away from debt-funded infrastructure spending and reduce reliance upon exports (in the face of further rounds of tariffs from the US and the West), means China’s growth is slowing, especially as domestic consumption seems slow to develop and take up the slack.

Fixed-income markets sense a deep-seated malaise, given how the 30-year government bond yield in China now stands below that of Japan – a sufferer until recently of a 30-year-plus debt deflation, itself the result of an epic, debt-fuelled speculative episode in equities and property in the mid-to-late 1980s. The yields on 10-year paper are close to converging as well.

Beijing is alert to the danger, as the authorities have already sanctioned interest rate cuts, lower capital requirements for banks to try and boost lending and incentives to stimulate residential property demand.

Money supply growth is picking up a little as a result, but December’s 7% year-on-year increase is barely sufficient to sustain China 5% annual GDP growth target.

More may be required, therefore, although China’s currency could come under further pressure if monetary policy eases quickly and bond yields continue to sink.

Beijing has a delicate economic balancing act, as it seeks to dodge a downward snake and climb an upward ladder. It is not on its own in this respect and, while it may seem old-fashioned, money supply could yet prove a telling indicator for macroeconomic trends elsewhere – including here in the UK.

MONETARY MAYHEM

In the 1980s, the economist professor Alan Walters was a huge influence on prime minister Margaret Thatcher. A monetarist, he advocated the theories of Milton Friedman, who argued that inflation is ‘always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ In other words, changes in the supply of money would affect its value, just as it would any other product.

Fast-forward 40 years and this no longer seems to be a fashionable view, but one look at the money supply growth chart for China may explain why its annual rate of inflation is all but zero.

A surge in money supply in the US and UK in the early part of this decade, thanks to the deployment of furlough schemes, welfare cheques, interest rate cuts and quantitative easing as a means of fighting the economic effects of Covid-19, was a likely contributor to the subsequent surge in inflation on both sides of the Atlantic.

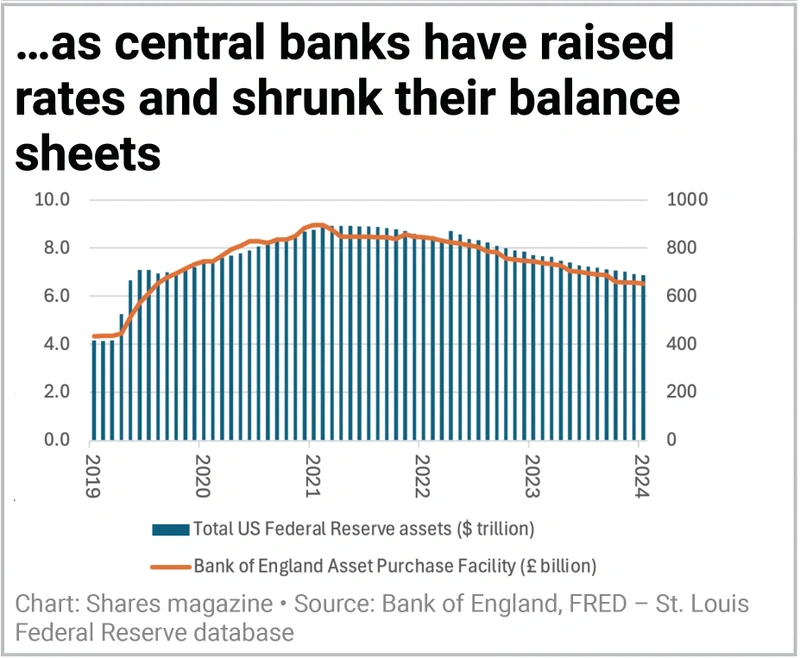

The US Federal Reserve and Bank of England then switched policy. They raised interest rates and stopped buying treasuries and gilts and started to sell them, with the result that yields have gone higher and the money supply taps have been tightened, if not quite cut off. Higher rates and quantitative tightening may have helped to cool inflation, at least if Friedman’s and Walters’ theories were correct.

LAGGING BEHIND

This all matters as China debates how to drag itself out of the mire, president Trump demands the US Federal Reserve cuts interest rates and the Bank of England debates how far and how fast it should reduce the headline cost of borrowing in the UK.

The Monetary Policy Committee was slow to act as inflation rose, and is equally likely to be slow to react as it cools, in a perfectly human attempt to counterbalance the prior error, even in the knowledge that monetary policy works with an 18-to-24-month lag.

Financial markets currently expect two, one-quarter-rate points from the Bank of England this year. Go too slow and inflation could stay above target, too fast and the economy could tip into recession.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Editor's View

Feature

Great Ideas

Investment Trusts

News

- US companies on course for highest quarterly earnings growth since 2021

- The factors driving Imperial Brands to 52-week highs

- Barclays set to deliver strong annual profit growth after doubling share price

- Mitchells & Butlers shares knocked by £100 million ‘cost headwinds’

- A return to growth in international markets in focus at McDonald's

- Markets brought back from the brink after planned tariffs put on hold

- Saba rebuffed as retail shareholders turn out for trust votes

magazine

magazine