This year’s record highs in the US, UK and German stock markets continue to make headlines, but another, much more unsung asset is also breaking new ground and that is gold, which hit $2,942 an ounce on 11 February.

The metal’s 44% surge in the past year has even outpaced the 31% increase in the combined valuation of the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ and gold has outperformed the septet even once their massive share buybacks and dividend payments are included in calculations.

| Capital gain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold | Alphabet | Amazon | Apple | Meta | Microsoft | NVIDIA | Tesla | Mag7* | |

| 3 years | 58% | 39% | 52% | 35% | 227% | 40% | 458% | 22% | 68% |

| 2 years | 56% | 97% | 139% | 51% | 312% | 57% | 528% | 78% | 114% |

| 1 year | 44% | 25% | 34% | 21% | 53% | (2%) | 85% | 81% | 31% |

Source: Refinitiv data. Mag7 based on change in aggregate market capitalisation of the seven stocks.

Even though gold has risen faster than Apple’s share price over the last one, two and three years, it still feels unfashionable to focus on gold, and it is easy to dismiss the case for including the precious metal in even the most balanced of portfolios.

As Warren Buffett succinctly put it in a speech he gave at Harvard in 1998, ‘Gold gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head.’

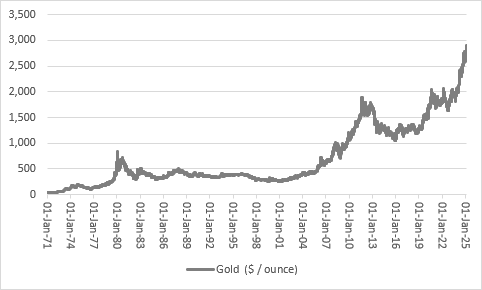

Yet, unusually, the market is shrugging off the Sage of Omaha’s words of wisdom and embracing gold instead in what seems to be the precious metal’s third major bull market since 1970.

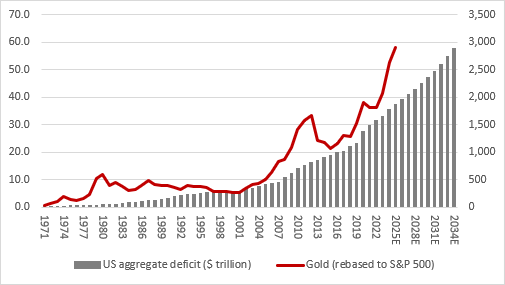

Source: LSEG Refinitiv data

The first came in the wake of President Richard M. Nixon’s decision to withdraw America from the gold standard in 1971. That move pulled down the curtain on the Bretton Woods monetary system that had prevailed since the end of the Second World War and ushered in a period of both unfettered government spending and inflation, the latter stoked in by two oil price shocks thanks to unrest in the Middle East. Central banks were slow to respond to inflation and the US Federal Reserve, for one, tried to cut interest rates too early and unleashed a second wave of inflation. The result was a surge in gold from $35 an ounce in 1971 to a peak above $700 in late 1980.

The second came in the early part of this millennium. Again, the narrative focused upon how central banks had lost control of the narrative, as they left interest rates too low for too long after the bursting of the technology, media and telecoms bubble in 2000.

Free and easy money, and loose regulation, facilitated a frenzy in property and complex, real estate-related debt instruments that turned into a crushing bust.

Western central banks had to cut interest rates to zero and launch both a range of unorthodox monetary policies and acronyms, including quantitative easing. Investors looked for haven amid the bank bail-out and central bank balance sheet expansion and found it in gold, which romped from barely $250 an ounce in 2001 to a new high of almost $1,800 by early 2021.

Now we have what looks like a third era in which gold is really starting to shine.

The metal dipped below $1,200 an ounce in late 2018 but has since marched inexorably higher. COVID-19, and more QE, more interest rate cuts and above all more government deficit accumulation all combined to persuade investors to warm to gold once more, as supply of the metal grew so much more slowly than the supply of money.

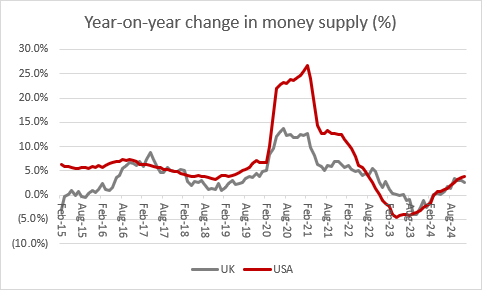

Source: LSEG Refinitiv data

Inflation spiked, central banks looked to be behind the curve as they raised interest rates too slowly and fiscal incontinence sparked worries that the authorities would have to try and keep headline rates low to help government service their soaring debts, whether inflation was falling back toward the 2% target or not.

Quite which of these issues is now the main driver of gold’s renaissance is hard to divine, especially as Donald Trump’s tariffs are prompting a debate about how inflationary (or stagflationary) they may prove to be, and how effective they may be at funding the new US President’s hoped-for tax cuts.

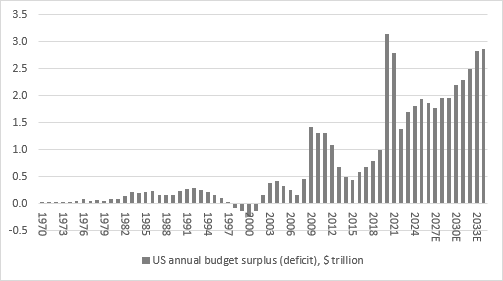

Nixon broke the gold standard so he could fund welfare programmes and pay for the Vietnam War and one thing that his move undeniably did was permit America to borrow.

America’s aggregate deficit has mushroomed over the past fifty years, and it has already begun to surge again in the fiscal year to September 2025, even as Trump has moved to rein in some of the spending associated with Inflation Reduction Acts and tackle what he sees as pork-barrel profligacy.

According to Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the US federal deficit for the first four months of the year to September 2025 is $838 billion. That is some $306 billion greater than in the equivalent period for fiscal 2024 and represents a figure higher than any annual deficit bar four in US history before 2018 (and those years were 2009 to 2012 as America worked to shake off the after-effects of the Great Financial Crisis).

The Congressional Budget Office’s latest forecast is for a $1.9 trillion deficit in fiscal 2025, the third-highest number in history, and for that figure to surge to $2.9 trillion by 2034. Heaven knows what would happen were an unexpected recession to hit home. That would force an increase in welfare spending and lead to a decline in tax income at the same time.

Source: LSEG Refinitiv data, FRED - US Federal Reserve database, Congressional Budget Office

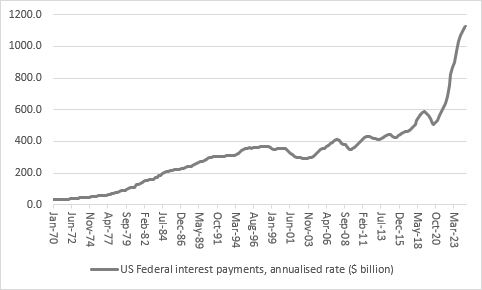

It is tempting to argue that this does not matter, and no-one cares, as evidenced by how Congress keeps on raising the debt ceiling, which is again drawing ever nearer at $36.1 trillion.

Nor will America ever default so holders of US Treasuries will always get their coupons, and their principal investment returned upon maturity.

However, further increases in the debt ceiling are inevitable and this raises the issue of how America funds the coupon payments and the maturity of its debts. The annualised interest bill now stands at $1.1 trillion and counting.

Source: FRED – St. Louis Federal Reserve database

America cannot afford to keep interest rates where they are for long and there is a risk that the Fed has to cut rates to keep the burden manageable and take risks with inflation (or even let inflation help salt down the debt/GDP ratio, if interest rates are kept below nominal GDP growth for long enough). Worse, it may even have to resort to Quantitative Easing (QE), or money printing, if creditors prove less tractable in their support of America’s spendthrift habits.

None of this may come to pass, and the Fed is currently shrinking its balance sheet, not expanding it. But someone, somewhere is reaching out for gold all the same, whether this is down to Trump’s tax policies, geopolitical concerns or even some central banks diversifying away from the dollar, for fear of what the US President may do next.

According to the World Gold Council, central banks added 1,045 tonnes to their reserves in 2024. That was the third year in a row when they gobbled up more than 1,000 tonnes of the precious metal and stories about how gold vaults have struggled to meet demand have begun to multiply.

Source: FRED - St. Louis Federal Reserve database, Congressional Budget Office, LSEG Refinitiv data

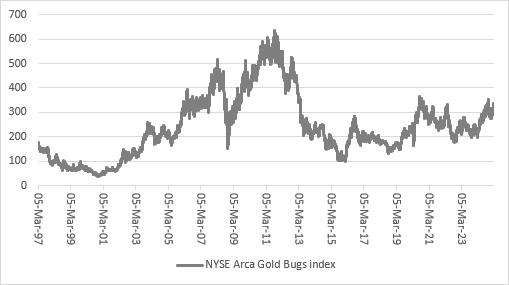

Equity investors are clearly less convinced about commodity traders, given how badly gold miners are performing.

The New York Stock Exchange ARCA Gold Bugs index is no higher now than it was in spring 2006, when the gold price was $550 an ounce, not $2,900.

Source: LSEG Refinitiv data

A wave of mergers and acquisitions has not fired their interest, either. Barrick Gold swallowed up Randgold Resources and Newmont snapped up Goldcorp in 2019; Agnico Eagle and Kirkland Lake Gold merged in 2021; in 2023 Agnico Eagle and Pan American Silver bought and split up Yamana Gold before Newmont pounced on Australia’s Newcrest; and in 2024 South Africa’s Gold Fields moved on Canada’s Osisko Mining. Even London got caught up the action last year, as AIM-quoted tiddler Shanta Gold and FTSE 250 index member both drew bids.

Sceptics will dismiss this as an attempt to manufacture growth and momentum where little or none exists, since gold output grows only slowly and the all-in sustained cost (AISC) of producing gold is rising, in no small part due to surging energy and staff costs (trends which rather dent gold miners’ perceived status as a hedge against inflation).

The gold miners themselves may see the modest share price performance opportunity, especially as profit margins and cash flows should benefit if the gold price maintains its current trajectory, although Mali’s demands for higher royalty payments and an increase stake in new projects highlight the risks involved. Sometimes even sitting on a gold mine is not a straightforward path to riches.

Ways to help you invest your money

Put your money to work with our range of investment accounts. Choose from ISAs, pensions, and more.

Let us give you a hand choosing investments. From managed funds to favourite picks, we’re here to help.

Our investment experts share their knowledge on how to keep your money working hard.

Related content

- Fri, 25/04/2025 - 14:52

- Wed, 23/04/2025 - 14:22

- Tue, 22/04/2025 - 10:44

- Thu, 17/04/2025 - 16:01

- Fri, 11/04/2025 - 17:57