Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Why America’s interest bill is so important and why no-one is talking about it

The US Federal Reserve is cutting interest rates for the first time since the pandemic-poleaxed year of 2020 in a welcome (and necessary) affirmation of the equity markets’ bullish narrative that inflation will cool, the American and Western economies will enjoy a soft landing (if they suffer any landing at all) and central banks will ease policy as a result.

This cheaper credit will, in turn, support growth, corporate earnings and thus share prices, and stock markets are sticking to the script as evidenced by the move higher in response to the central bank’s easing of monetary policy.

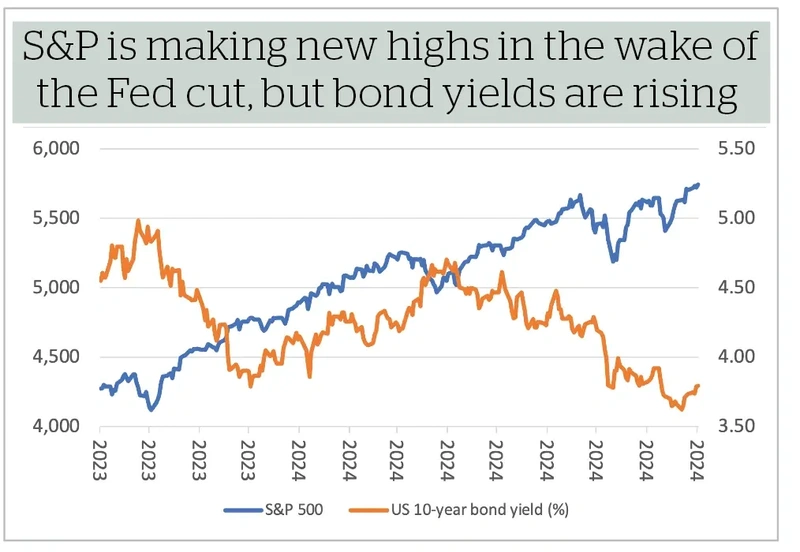

Granted, the S&P 500 stands just 1.5% higher than it did in July, but bulls will welcome a new peak all the same, especially as the US Treasury market is not necessarily welcoming Fed’s policy pivot.

The US 10-year yield is rising, not falling, although it has already fallen sharply. As such, this could yet be a case of the market pricing in the cut long before it actually happened.

The equity market has also traveled a long way, and this again could explain why the S&P 500 has responded very calmly to chair Jay Powell’s policy pronouncement.

Equally, it may be worth asking what prompted the Fed to go for a half-point rate cut in September when it felt comfortable doing nothing in July, because something has clearly changed.

This matters because prior rate cycles show the equity market welcomes rate cuts so long as a recession does not then follow and the starting point valuation is not egregious either.

Both of those conditions applied in 2000 and 2007, which was why rate cuts did not stop a bear market from breaking out and those downcycles are outliers compared to historic averages.

PAYROLLS PROBLEM

The US Federal Reserve has two mandates – keeping inflation stable (at around 2%) and maximising employment.

Powell’s latest speeches suggest the Federal Open Markets Committee feel it is getting inflation under control, as does the summary of the US central bank’s latest economic projections.

This means jobs (and by extension a weaker economy) are now the focus, even if the Atlanta Fed GDPNow service is forecasting a very respectable annualised growth rate of 2.9% for the third quarter of 2024 (after 3% in Q2 an 1.6% in Q1).

That does not suggest major weakness is on the horizon, and nor do analysts’ consensus forecasts for earnings growth from the S&P 500 of 10% for 2024 and 17% for 2025.

Yet the unemployment rate has ticked up by nearly one full percentage point from the lows and job vacancies have dropped by a third from their 2021 peak.

As a result, the ratio of vacancies to unemployed workers in America is down from a high of 2.03 times to 1.07 times.

This data could be a result of summertime blues, or even the massive disruption caused in southern states by Hurricane Beryl back in July, but it could suggest something more malign.

The monthly non-farm payroll numbers have been subjected to regular negative revisions for 18 months, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics admitted that America added 818,000 jobs fewer than originally thought in the year to March 2024, a third of the published total.

Downward revisions usually occur when the US economy slows and upward ones when it grows.

BORROWING BLITZ

The Fed’s own economic projections sweep aside these concerns, as no real deterioration is expected in unemployment from here onwards – a scenario that fully ties in with the ‘soft landing’ scenario but not really one which merits a deep, one-half-point rate cut.

Perhaps other factors are at work – treasury secretary Janet Yellen is now publicly discussing the need to reduce the interest bill on the ever-growing US federal debt mountain, which is running at $1 trillion on an annualised basis, a sum that exceeds the defence budget.

Heaven help the US deficit if a recession unexpectedly reduces the tax take and increases welfare spending.

If the White House and Congress cannot (or will not) cut spending or raise taxes when the economy is robust, then the only alternative is to try to lower the interest bill on the borrowing.

That could mean playing fast and loose with inflation, but inflation boosts nominal GDP and thus helps to flatter debt-to-GDP ratio calculations, too.

Perhaps the outcome is greater volatility in inflation, and by extension interest rates and government bond yields, something that does not sit easily with the prevailing equity and bond market narrative.

While that may only become an issue in the second half of next year, when the year-on-year comparisons for the consumer price index come off a less testing base, the gold price does not seem to be waiting around to find out.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

magazine

magazine