Archived article

Please note that tax, investment, pension and ISA rules can change and the information and any views contained in this article may now be inaccurate.

Five key lessons to note from 2024

It’s ingrained in us as investors that the best way to get superior, risk-adjusted long-term returns is to distance ourselves from the crowd and seek out value.

That approach has always needed courage and patience, and 2024 has proved to be a particularly fierce test of this discipline for the simple reason that what worked last year worked well again this year.

It did so because the consensus macroeconomic view played out exactly as expected – inflation cooled, there was no deep economic downturn (or even a downturn of any real kind) and interest rates started to fall.

In sum, equities did well (again), led by technology and AI-related names (again), with the result that the US stock market outperformed, spearheaded by the Nasdaq (again).

Japan’s benchmark indices did better than those of Europe, which in turn generally did better than those of the UK, while emerging markets lagged (even as China put on a bit of a wiggle towards the end of the year).

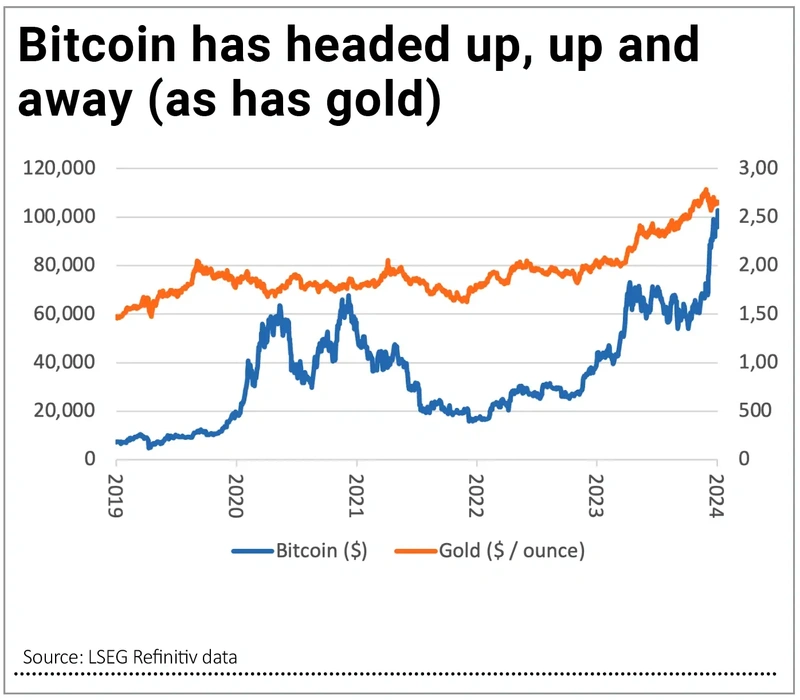

Holders of benchmark, 10-year government bonds lost money for the third year in four on both sides of the Atlantic, while commodity prices rose on average for the fourth year in five. Oil did poorly, gold did well, and Bitcoin went bananas (again).

These trends leave 2021-22 looking like a post-Covid-19 aberration and suggest the long-term trend of cheap energy, food, goods, labour and (above all) money that began in the early 1980s is reasserting itself.

It’s therefore worth thinking about what happened in 2024 and why, and whether these trends are set to continue into 2025 and beyond.

COOLER INFLATION

Inflation dipped back to, and even briefly below, central banks’ 2% target in the UK and EU and nearly got there in the US based on the official consumer price index and the US Federal Reserve’s preferred personal consumption expenditure benchmark. That gave central bankers the room they needed to start cutting interest rates.

That said, much of the improvement in inflation came from oil and energy, as well as goods, where unblocked supply chains helped supply and the lagged effect of higher interest rates took some of the edge off demand.

Services inflation remained sticky and could yet prompt workers to demand more in the way of pay increases, so perhaps central banks shouldn’t be too gung-ho just yet.

STEADY GROWTH

A global recession failed to materialise in 2024, despite disappointing growth from China, Japan, Germany and France (four of the globe’s seven largest economies).

India took up some of the slack, the UK emerged from 2023’s shallow downturn and the US once more led the charge.

The Biden administration’s CHIPS and Inflation Reduction Acts buoyed output and American consumers kept spending, helped by rising house and stock prices.

America’s latest debt-ceiling breach gave no-one pause for any particular thought, even as the deficit soared, and president-elect Trump’s plan to raise revenues through tariffs has provoked as much concern as it has positive comment.

If Elon Musk succeeds in cutting US government spending, and Trump rolls back the Inflation Reduction Act, there could yet be some (unpleasant) unintended consequences.

INTEREST RATE CUTS GALORE

A tally of 175 interest rate cuts worldwide in 2024, compared to just 28 rate hikes, tells a clear story.

The UK, Japan and China all added fiscal stimulus to fresh monetary impetus, and you could argue the US did as well given how the Federal deficit grew by another $1.8 trillion to an all-time high of $36 trillion.

The question for 2025 is whether a combination of sticky inflation, steady growth and ballooning government debts (and rising sovereign bond yields) crimp central banks’ room for manoeuvre and force the pace of rate cuts to slow or, at the extreme, come to a halt.

BITCOIN AND GOLD BOTH SHONE

Gold and (most spectacularly) bitcoin set new all-time highs, while silver hit a twelve-year high.

Such demand for havens does not sit comfortably beside equities’ core scenario of cooling inflation, steady growth and lower interest rates.

It may be the result of fears that central banks are playing fast and loose with inflation, or that ever-growing sovereign debts are persuading them to cut rates (and ease governments’ interest bills) whether they feel it is appropriate or not.

President-elect Trump’s enthusiasm for all things crypto, his planned deregulation drive and the departure of Gary Gensler from the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) mean bitcoin is up 40% in barely two months, helped by what can be seen as increasingly reflexive ETF flows (the higher bitcoin goes, the more buyers appear), in a clear win for momentum over value investors.

SOVEREIGN BONDS DID POORLY

Another slightly discordant note comes from the sovereign bond market, and this matters because the 10-year bond represents the local risk-free rate and thus the benchmark minimum return which is acceptable from any investment.

Yields on 10-year paper rose (and prices fell) despite interest rate cuts, suggesting the bond vigilantes are becoming nervous over governments’ debt piles in the US, UK and EU.

The question is whether there is political or public appetite for the tax increases and spending cuts needed to fix them, in the absence of growth or inflation reducing those growing debt-to-GDP and interest bill-to-total spending ratios.

Anyone who bought 10-year bonds in 2020, when central banks were indiscriminate buyers thanks to COVID-fighting QE schemes, has suffered, to perhaps offer a reminder that valuation always matters – in the end.

In January, we shall look at what the key macroeconomic trends in 2025 may be and how they in turn could shape the performance of investors’ portfolios.

Important information:

These articles are provided by Shares magazine which is published by AJ Bell Media, a part of AJ Bell. Shares is not written by AJ Bell.

Shares is provided for your general information and use and is not a personal recommendation to invest. It is not intended to be relied upon by you in making or not making any investment decisions. The investments referred to in these articles will not be suitable for all investors. If in doubt please seek appropriate independent financial advice.

Investors acting on the information in these articles do so at their own risk and AJ Bell Media and its staff do not accept liability for losses suffered by investors as a result of their investment decisions.

Issue contents

Editor's View

Feature

Great Ideas

Money Matters

News

- Can Chemring profit play catch-up after slow start to the year?

- Why Rolex seller Watches of Switzerland has clocked up a 40% gain in six months

- China eases monetary policy ahead of Trump 2.0 and global tariff war

- Budget impact on UK firms tops £1 billion as hiring slows

- Frasers shares down 30% year-to-date as Budget blues bite

magazine

magazine